Leper Hospital

Elgin

There is little doubt that the first 'hospital' in Scotland was built by the Romans. In 1958, a legionary hospital (valetudinarium) was unearthed at Inchtuthil, near Perth. It had long corridors around a central court and there were some sixty rooms where up to 300 sick and wounded Roman soldiers could be restored to health. This is, in fact, the earliest hospital known in the whole of the British Isles. The fortress was built in A.D.83 as the advance headquarters of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the Roman governor of Britain. It provided the resources necessary to support the 5,000 or so men who were out garrisoning the Highland Line. However, the Legionary forces were withdrawn to the Danube limes after only six years at Inchtuthil, leaving behind a large complex of buildings comprising, barracks, administrative offices, officers' quarters, a great workshop and a hospital.

But this was a hospital in the modern sense of the word - a place for the sick. The medieval hospital, examples of which we see inhabiting the landscape, both in rural as well as urban locations, was more properly, known as an hospitium - a place which offered hospitality and lodging to a wider clientele, including the aged and infirm, travellers and the poor, in addition to the sick. It had features which we would today recognise in an inn or a care home.1 But we should also remember that, in one sense, these medieval institutions were the very opposite of their modern counterparts - they were singularly 'religious' (rather than 'lay') in their outlook and life was regulated very much in accordance with monastic custom.

This conception of a 'hospital' persisted through the Middle Ages. For example, when a charter was granted to the hospital at Flixton [Yorkshire], during the reign of Henry VI, it was stated that the building was to be used "to preserve travellers from being devoured by the wolves and other voracious forest beasts."2 Scotland presented a no less perilous prospect for travellers!

In the Middle Ages, there was a significant increase in the number of leprosy cases across Europe, to the point that the disease had become a routine feature of life by the 11th century. At that time the social reaction to leprosy was often fear, and people infected with the disease were thought to be 'unclean' or morally corrupt. However, beliefs about the disease were complicated. Some believed leprosy was a punishment for sin, but others saw the suffering of lepers as similar to the suffering of Christ, bringing them closer to God than other people. Care in religious leper hospitals focussed as much on spiritual needs as on the physical symtoms of the disease and a chapel was an essential component of a leper community.

A Leper Hospital was not a hospitium in the general sense since it only provided for the well-being of those afflicted by Leprosy - which in the Medieval Age, was considered to be a dreaded disease requiring the sufferer's immediate removal from the local community to a facility which best resembled the 'isolation' and 'fever' hospitals of the Victorian Era.

Many of these leper houses were known as 'lazar-houses' because they had often been founded and administered by the Order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem. However, over the course of time, the terms 'lazar' and 'lazar-house' came into general use and did not necessarily indicate any link with the Order. In Elgin there is still a Lazarus Lane which became so named because the lands here were once 'owned' by the "fratribus Sancti Lazari juxta muros Jerusalem."3 Because of the risk of infection, lazar-houses were usually built on, or beyond, the outskirts of the town and normally consisted of a group of cottages and a chapel. Cochran-Patrick observed that, "To ensure public health, all lepers and infected persons were to be thrust out by the serjeants of the town beyond the walls, but a hospital was provided outwith the town by voluntary contributions for such unfortunates."3a As a matter of routine, lepers were required to wear particular clothes that marked them out to the general public and gave warning of their approach, and they routinely carried a bell or a 'rattle' which would amplify the warning. But many people believed that, although physical contact should be avoided, lepers were in fact closer to God and that they were suffering 'purgatory' on earth which would result in a less dreadful afterlife and would get to heaven sooner than might otherwise have been expected.

On admission, the leper was sometimes required to take an oath following which he might be taken to the altar of the hospital's chapel to be sprinkled with holy water and receive a blessing. Of course, lepers were not expected to recover, although a small number did.

Location.

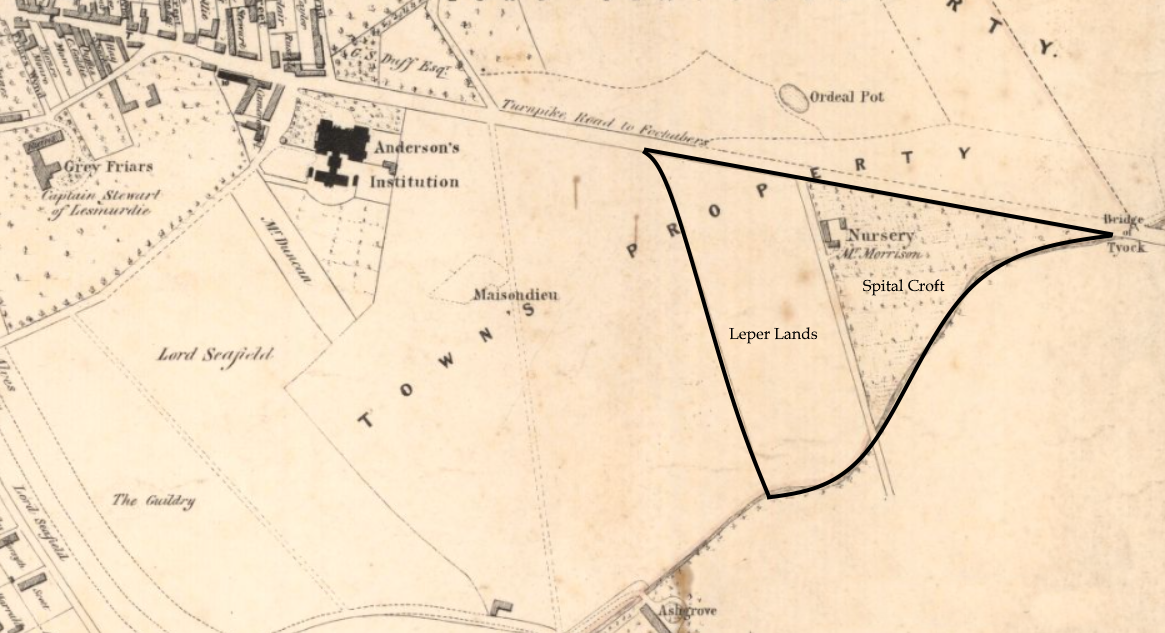

In Elgin, the exact site of the buildings of the Leper Hospital, particularly the location of the chapel, cannot now be accurately located, but the lands which surrounded it are reasonably well known. They lie immediately to the east of the lands of the Maison Dieu, between the King's Highway to the north and the Burn of Taock to the south. The Ordnance Survey places the house itself at

The 'nursery' mentioned in the text is shown.

An important feature of a Leper House was that it should be located as close as possible to a main road or at a junction of routes or pathways. This meant that the lepers could beg for alms from as many passing travellers as possible and we can see that, in the case of Elgin, the leper house was adjacent to the King's Highway which was the main route in an out of the town. In this way the lepers would have been able to maximise their meagre 'income'.

Very little is known from the written record of the history of the Elgin leper hospital, neither the date of foundation nor of its final closure. One of the first mentions of it occurs about 1391, when certain lands called Spetalflat, beside the house of the 'Lepers of Elgin', is recorded and Cowan and Easson take this date as being the date of its foundaion.5 However, it is quite probable that the foundation took place somewhat earlier, particularly since the same authors give a date of 1224-6 for the foundation of the leper hospital at Rathven, in Banffshire, which is at no great distance from what was the cathedral city and Royal Burgh of Elgin. Such an earlier date would put us into that period when the Bishop of Moray (Andrew de Moravia) had started building his new cathedral and would have been keen to establish the burgh on a par with others in the country. It seems flippant to suggest that Andrew would have been keen to 'rid' the town of lepers for aesthetic reasons, but his faith would have required him to follow the examples other towns and to make provision for the lepers outwith the burgh 'limits'. Elgin was to be an example to the nation and Andrew had the backing of one of the most powerful families in the whole of the north of the country to help him achieve his objective. There is little doubt that he had the ambition and determination to place Elgin amongst the great cathedral cities of the nation.

1541-2. At a much later date, an entry in the Burgh Court Book, dated 8th March 1541-2, records that, "The quhilk day the prouest (provost), etc., he set the croft of Tayok syid and Spittel croft to John Vat, Androu Gibson and Alexander Williamson for iii zeris for fourty sillingis be zeir."6

1548. At the Head Burgh Court held on 13th November 1548 it was recorded that, "The Spittal croft - the thred [third] part to Andro Gibsoun and the remanent to William Auldcorne."7

1650. Some one hundred years later, again in the Burgh Record Book, this time dated 5th June 1650, we find, "William Milne resigns his Spittall croft lying betuixt the kings highway that passes fra the east poirt of the bruch to the bridge of Barmuckatie at the south, the channonrie crofts of the Cathederall kirk of Murray at the north, extending in lenthe fra the burne of Tayok at the east to the Lyper lands at the west, in favour of Alexander Dunbar."8

Simpson and Stevenson suggest that the Hospital "probably discontinued at the Reformation, though [the] designation 'leper' remained attached to its former acres in later title deeds of adjacent properties."9 They continue, "this may well have been the case but there are many instances where a leper hospital was taken over by the town council and continued to serve the needy well into the seventeenth century. It could e that this was the case in Elgin, but there is no evidence to support the idea." However, as we shall see, they were wrong.

1863. In the 1863 edition of Black's Morayshire Directory, there is the following:

II.-AUCHRAY'S OR PITULLIE'S MORTIFICATION.9a

The charity under this title was instituted by William Cummine of Auchray and

Pitullie, who, by deed of mortification, dated the 12th October, 1693, bequeathed a

sum of money to be laid out in the purchase of lands, the rents of which were to be

applied for the maintenance of four poor old decayed or broken merchants, being

residenters within the burgh, and burgesses thereof. With part of the amount the

" Leper" lands had been purchased previous to the date of the deed of mortification,

and since that time the four crofts called the "hospital crofts," and a rood of burgh

land, have been 'purchased' for the purposes of the charity. It might be more accurate to say that the rood of Town land had been allocated to the Charity so as to augment the total rental income available to it. The balance, £2022 17s. 9d.

Scots, or £168 15s. sterling, lies in the hands of the Town Council, for which interest

at 5 per cent, is paid yearly into the funds of the charity. The lands are in the

possession and under the management of the Magistrates, and the:-

| Present rental is | £79 13s. 9d. |

| Interest on £168 15s. in town's hands | £ 8 8s. 9d. |

| Total | £88 2s. 6d. |

This sum, after deducting local taxes and other burdens, is divided equally among

the four decayed merchants presented to the charity. The presentation is vested in

the donor's heirs and successors jointly with the Magistrates of Elgin, who alternately have the right of nomination.

In 1863, the incumbents were— James Galium, Thomas Andrew, and James Cruickshank. There is also a vacancy.

Allowance to each last year, £21 0s. 7d.

It is quite clear from this information that the "Leper" lands had been purchased just previous to 12th October, 1693, and, at some point afterwards, the Town also bought the four crofts, which from their name - "the hospital crofts" - were formerly part of the Leper Hospital. There may have been other crofts that had been part of the Hospital, but this is not made clear. The Town also purchased an additional rood of land to add to the income of this Charity.

1891. In Mr. Laclan Mackintosh's book, published in 1891, he gives the following information:

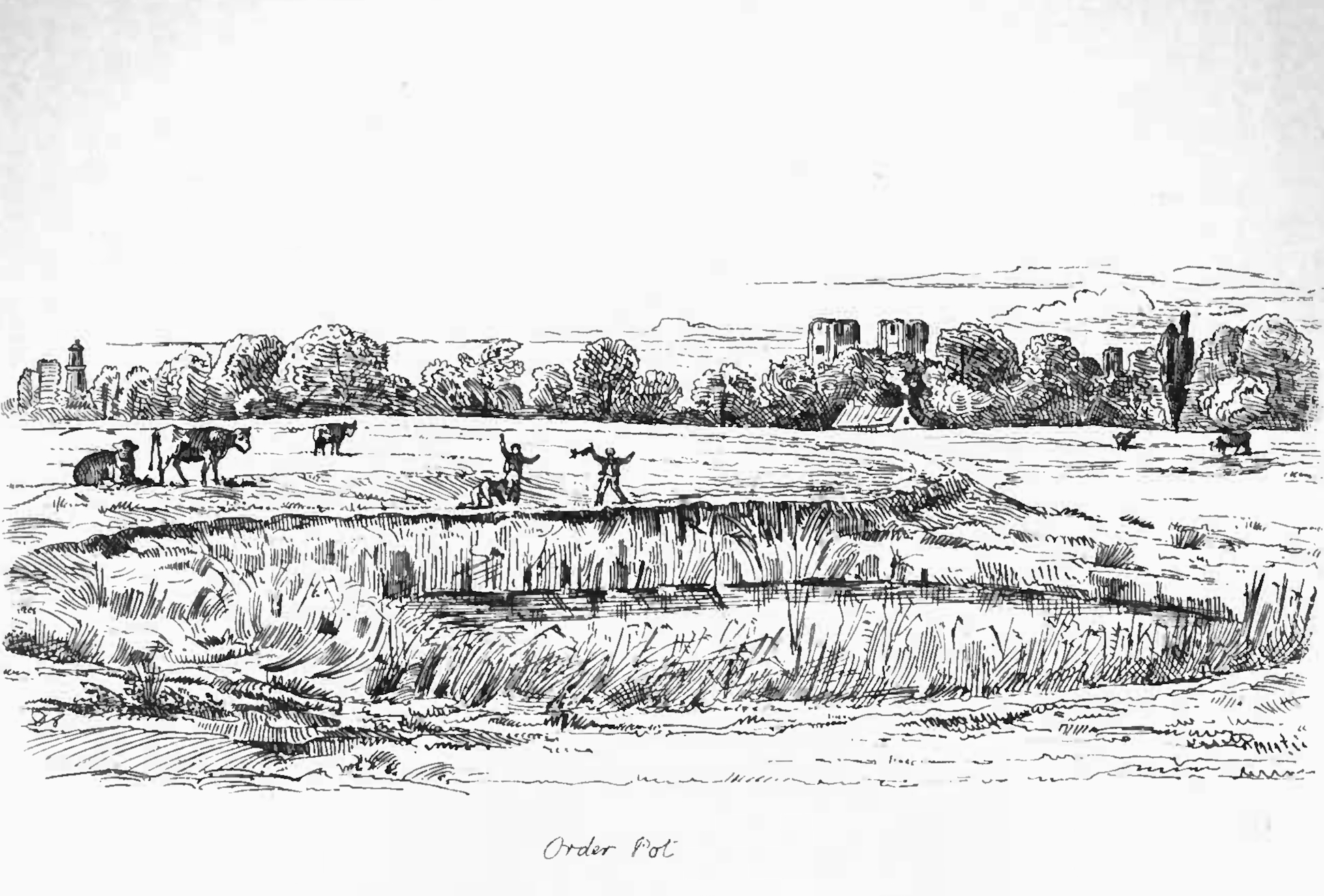

LEPER HOUSE. - The Leper House referred to in the foregoing notes on the Ordeal Pot is mentioned in a letter by Mr. John Lawson, Oldmills, to Mr. Isaac Forsyth, as having stood on a piece of ground on the east side of and near the Order Pot. This accounts for the words in the preceding notes — “ Ane leper came doun frae ye hous," i.e., came down to the bank of the pool. Mr. Morrison's nurserymen, during the winter of 1850, came on the foundations of this Leper House, which was built of rounded stones or boulders, and blue clay, of which there were about forty cart loads. The locality of this house is corroborated by a statement made by Mr. Robert Grigor, [writer and antiquarian], in the year 1838 - " that he remembered to have seen part of the bottom stones of this hospital dug up on the croft occupied by Mr. James Coull opposite that part of the Leper lands named Pinefield." This hospital stood on the east side of the railway embank ment and immediately opposite the Ordeal Pot.9b

At the time of the creation of the Ordnance Survey 'Name Books', towards the end of the 19th century, the lands which had belonged to the Leper Hospital were known as Pinefield Nurseries, the property of Mr George Morrison. The property was described as, "An excellent and extensive nursery at the east end of the city principally for the culture of the different varieties of ornamental trees, flowering shru[bs] etc. There is another detached nursery between Institution Road & the Morayshire Railway but it has no particular name." It was also owned by Mr Morrison.10

In 1993, at

OS Six-inch, 1840-1880 (county layers).

Elgin Leper gives witness at Witchcraft Trial.

From the Burgh Records there is evidence that a significant number of trials for witchcraft took place in Elgin about the year 1560. The crimes of which the poor creatures were accused show, in a very striking manner, the superstitious belief of the age. There are no well-authenticated facts at that date of the mode of trial; the manner of punishment, however, was awful. "The comptar, viz., Andro Edie, discharges him of 40s., debursed be him at ye town's command for the binners (ropes) [bindings] to ye wiffes yat war warditt in ye Stepill for witches , in summer by past.' There must have been several that summer consigned to the "Stepill" ( Order Pot ) when the sum of 40s. was required to be paid for binners [binders] to bind them. [Mackintosh may be wrong here in identifying "Stepill" with the Order Pot since the witches are said to have been warded within the Stepill, since even charitable Elgin folk would not have kept (warded) these poor women within the waters of the Pot. I believe it is much more likely that "Stepill" means the steeple of St Giles Old Kirk, here being used as a prison. But it is difficult to be certain.] What happened to these 'witches' is revealed in the following passage:

"The whilk day ane great multitude rushing through the Pannis Port surroundit ye pool, and hither wis draggit through ye stoure ye said Margory Bysseth in sore plight, wid her grey hairs hanging loose, and crying Pitie, pitie!' Now Mr. Wyseman, the samin clark who stood up at her tryal, stepped forward and said - 'I kno thys womyan to have been ane peaceable and unofending ane, living in ye privacy of her widowhood, and skaithing or gainsaying no ane. Quhat have ye furthir to say again her? 'Then did the Friars' agent repeate how that she did mutter her aves backward , and others that the maukin (hare) started at Bareflat, had been traced [followed] to her dwelling, and how the afore said cattel had died by her connivaunce. But shee hearing this, cried the more, Pitie! Pitie! I am guiltlesse of ye fause crymes, never sae muche as thought of by me. 'Then suddenlie there was ane motion in the crowd, and ye people parting on ilk syde, ane leper came doun frae ye house, and in ye face of ye peopel bared his hand and his hale arm, ye which was wythered, and covered over with scrufs most pyteous to behold, and said - 'At ye day of Penticost last past, thys woman did give unto me ane sheel of oyntment, with ye which I anoynted my hand to cure ane imposthume whiche had come over it, and beholde, from that day furthe untyll thys it hath shrunke and wythered as ye see it now. 'Whereupon the croud closed rounde and became clamorous; but ye said Margory Bysseth cried pyteously that God had forsaken her - that she had meanyed gude only, and not evil - that the oyntment was ane gift of her husband, who had been beyond seas, and that it was a gift to him from ane holy man and true - and that she had given it free of reward or hyre, wishing only that it mote be of gude; but that gif gude was to be payed backe with evil, sorrow and gif 'Sathan mot not have owin.' Whereupon the people did presse roun and became clamorous, and they take the woman and drag her, amid mony tears and cryes, to ye pool and crie, To tryal! to tryal! 'and soe they plonge her into ye pule. And quhen, as she went doun in ye water, ther was ane gret shoute; bot as she rose agayn, and raised up her armes as gif she wode have come up [got out], there was silence for ane space. When again she went doune with ane bublinge noise, they shouted finallie, 'To Sathan's Kyngdome she hath gone!' and forthwith went their ways.12

(from Rhind's Elgin, 1839.)

1. Their name was derived by the Latin adjective hospitalis - concerned with hospites or guests. These "guests" were any persons in need of shelter. Return to Text

2. Dainton (1961), p. 17; Pat. 25 Hen. VI. p. 2. m. 17. In Dugdale's Monasticon Flixton Hospital is said to have been also known as "Carman's Spital" and was founded by an Anglo-Saxon knight called Acehorne for an "Alderman and fourteen Brothers and Sisters." [Dugdale, VI, p. 613-614] A "carman" was a carter. Return to Text

3. R.E.M., no 236, p. 304. Return to Text

3a. Cochran-Patrick (1892), pp. 116-117. Return to Text

4. Mackintosh (1914), p. 22. Return to Text

5. Cowan and Easson (1976), p. 78; R.E.M., no. 7, p. 29. Return to Text

6. Crammond (1903), p. 69. Return to Text

7. Crammond (1903), p. 94. Return to Text

8. Crammond (1903), p. 85. Te implication here is that the Spittal Croft and the Leper Lands were two separate but adjacent pieces of land. Return to Text

9. Simpson and Stevenson (1985), p. 35. Return to Text

9a. Black's Morayshire Directory (1863), p. 92. Return to Text

9b. Mackintosh (1891), p. 181-182. Return to Text

10. O.S. Name Books, [OS1/12/11/20] Return to Text

11. Batey (1993), p. 40. Return to Text

12. Mackintosh (1891), p. 179-180. Return to Text

Batey, C., (ed.) (1993) 'Discovery and Excavation in Scotland, 1993,' Council for Scottish Archaeology.

Cochran-Patrick, R.W. (1892) Medieval Scotland: chapters on Agriculture, Manufactures, Factories, Taxation, Revenue, Trade, Commerce, Weights and Measures, Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons.

Cowan, I. & Easson, D. (1976) Medieval Religious Houses, Scotland, London: Longman. https://archive.org/details/medievalreligiou0000cowa/page/n5/mode/2up (accessed 4/08/2023)

Cramond, Wm. (1903) The Records of Elgin, 1234-1800, Volume 1, Aberdeen: printed for the New Spalding Club.

Dainton, C. (1961) The Story of England's Hospitals, London: Museum Press.

Innes, C. (1837) Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis: e pluribus codicibus consarcinatum virca A.D. MCCCC, cum continuatione diplomatum recentiorum usque ad A.D. MDCVVIII, Edinburgh: for the Bannatyne Club. [R.E.M.]

Mackintosh, H.B. (1914) Elgin Past and Present: a Historical Guide, Elgin: J.D. Yeadon. https://archive.org/details/elginpastpresent00mack

Mackintosh, L. (1891) Elgin Past and Present: a Guide and History, Elgin: Black, Walker, & Grassie. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Elgin_Past_and_Present.html?id=RBJBAQAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed 06/09/2023)

Oram, R. (2012) Alexander II, King of Scots 1214-1249, Edinburgh: Birlinn, Ltd.

Oram, R. (2021) 'The Dominicans in Scotland, 1230-1560,' in E.M. Giraud & J.C. Linde (eds.) A Companion to the English Dominican Province: From its Beginnings to the Reformation. Companions to the Christian Tradition, 97. Leiden: Brill. pp. 112-137. href="https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004446229_005 (accessed 18/08/2023)

Simpson, A.T. & Stevenson, S. (1982) Scottish Burgh Survey: Historic Elgin, the Archaeological Implications of Development, Department of Archaeology Glasgow University.

Black's Morayshire Directory, including the upper district of Banffshire, 1863, Elgin: James Black at the Elgin Courant Office.

O.S. Name Books, Morayshire, 1868-71, Volume 11. [OS1/12/11/20] https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/morayshire-os-name-books-1868-1871/morayshire-volume-11/20 (accessed 21/08/2023)

e-mail: admin@cushnieent.com