Elgin Deanery

Urquhard

Parish Church: OS Ref: NGR NJ 289626 H.E.S. No: NJ26SE 9 Dedication: St Margaret.

Associated Chapels: (None known.)

As we are often required to do, we must start by considering this parish's place-name - Urquhard. The reader will regularly find the name spelled also as Urquhart. There are, in fact, three churches bearing the same name in the north of Scotland and this often leads to a measure of confusion amongst historians. There is the church we are presently dealing with, which lies within the Deanery of Elgin, at a location about 5 miles east of Elgin. Then, there is the church of Urquhart (also known as Kilmore), which lies on the shores of Loch Ness, in the Deanery of Inverness

The older form of the name is Urquhard which stems from the seventh-century name Airdchartdan, thought to be a mix of Gaelic air meaning 'by' or 'beside', and an old Welsh/Brythonic word cardden signifying a 'thicket' or 'wood'. The Scots Gaelic form is Urchardan.1 In order to avoid confusion, we have determined to use the Scottish Gaelic form of the place-name for this parish (and the Priory) - Urquhard - in an attempt to remove one of the sources of confusion. We have chosen to retain the Urquhart form of the name for the other two parishes mentioned above.2

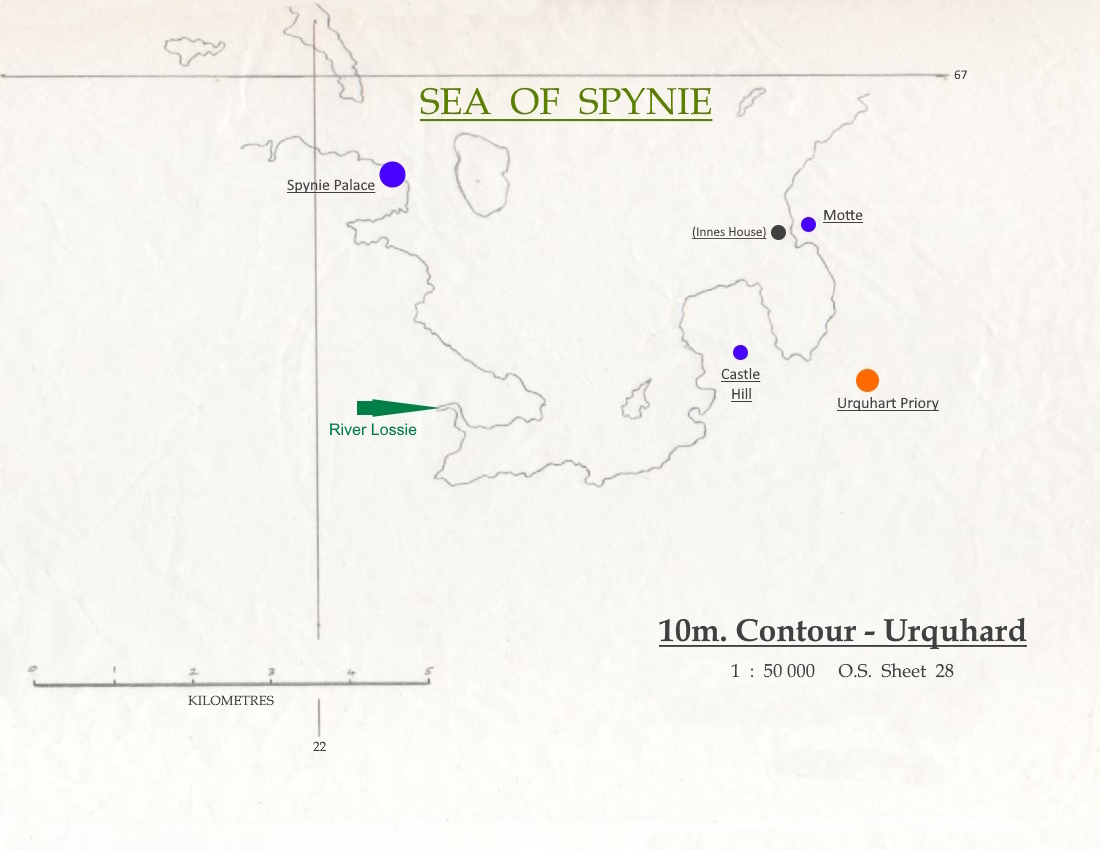

Even a simple review of the Ordnance Survey map of the environs of Urquhard is enough to provide convincing evidence that the area has been of some considerable significance from the very earliest of times. The present village of Urquhard lies at the hub of a collection of notable sites which have been dated to pre-history. Indeed, within a 3km. radius, we have a concentration of find-sites which has little to equal it for many miles.3 It is realistic to argue that in these prehistoric times, the local inhabitants tended to group in the Urquhard area rather than in the area of what is now Elgin. This should not surprise us since much of the land around Elgin was (and still is!) notoriously boggy, whereas Urquhart sits on good dry soil which, most importantly, lay on the fringes of the Sea of Spynie.4

This 'importance' held true throughout the Prehistoric and Roman eras, up to the so-called Dark Age period, and Urquhard (along with nearby Meft

Any reader who wishes to gain a greater appreciation of the importance of Urquhard in the prehistoric 'record' is urged to read the Rev. James Morrison's paper.

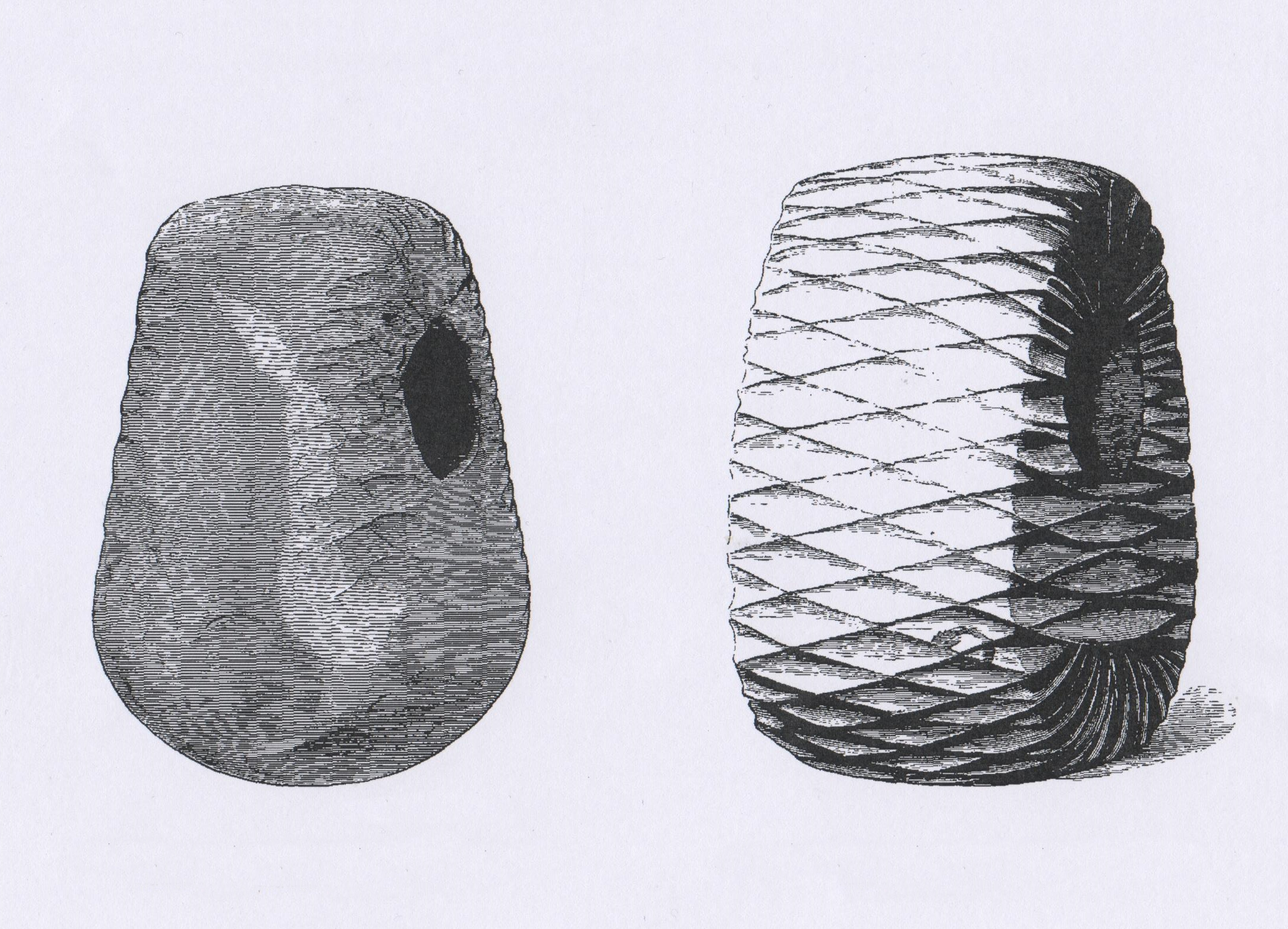

© National Museum of Scotland (000-100-036-530-C)

There are also old traditions telling that a Chistian community of the Early Church (muinntir) existed here at Urquhard, a long time before the priory was established. This is not just 'folk-lore' since we know that missionaries of the Early Church were active in this area (see St Andrews) and there are other 'indicators' on the ground. The farms on whose lands the Priory stood are still known as Easter and Wester Clockeasy, a name which seems to have no easy interpretation. However, many now agree that the original form of the name was Clach-Iosa from the Gaelic Clach or Cloch meaning 'stone' and Iosa meaning 'Saviour' or 'Jesus'.7 This has led to a number of suggestions, principally that there was a 'religious stone' here, which may have been some form of 'sacred' altar. If we accept Mr. Matheson's suggestion, then it would appear that there was a link here with early Christianity which, in turn, would lend support to the idea that there was an Early Church community in the vicinity long before the advent of the Priory. The fact that from prehistoric times, this was an important, high-status, population centre, would lead us to believe that it probably acted as a 'magnet' to the ancient wandering missionaries or 'peregrinatoris'. It would be far from surprising to find that what started as a traditional belief is, indeed, grounded in fact.

When the newly-fledged Kings of Scots finally subdued the "wild men o' Moray" and their leader (who himself was often regarded as a King in his own right), many of the lands of Moray were given by the 'new' Royal family to their favourites, both secular and religious. The lands of Urquhard were given to the new Royal abbey of Dunfermline at the time of its foundation, and this gift is confirmed in 1182.9 Somewhat later, the abbot and his community decided to create a daughter-house on these lands in order that they could be better managed and also to provide a leadership training-ground for his monks and a 'holiday' location for the older and more venerable members of the community where they could engage in religious 'retreats' away from the hustle and bustle of the mother-house.

The first church at Urquhart would have been a 'crude' affair by modern standards. It is supposed to have stood within the churchyard at the edge of the village and was dedicated to Saint Margaret, mother of King David, who was so instrumental in lending his support and financial resources to the establishment of the Priory. The venerable Bishop Pocock commented, "… near the Church of Urquhart, I was met by Sir Harry Innys who showed me the [parish]Church. It is of the old Saxon Architecture with narrow windows."9b It has always been difficult to find building-stone within the parish and even in the 19th century when a doo'cot was constructed within the garden of the Manse, it was built using 'clay-dab' - a composite of clay, straw and small pebbles - which was much used in domestic buildings in the Urquhart/Garmouth/Spey Bay area. Timber was also used, as is recorded at the "King's Hall" at Meft

The parish church was part of the 'property' of the Priory and it would appear that it was served by the members of the community. This also meant that the church had no 'parish lands' of its own since everything belonged to the Priory. From a charter of 1237, it is clear that the Priory had a three-fifths share in the following lands "from time immemorial" - which would seem to imply from its foundation - whilst the church of Eskyl [Essil] had the remaining two-fifths share. In the charter the church of Eskyl's share is transferred to the Priory in return for an annual payment of "twenty-four merks Stirling," one half to be paid at the feast of Pentecost, and the other half at the feast of St Martin in winter. The charter was signed at Kenedor [Kinneddar], 8th May, 1237.

In 1561, the Queen rewarded ger trusted friend, George Seton, 7th Lord Seton, with the stewardship of the estates which had belonged to Pluscarden Priory, and which included those lands which had belonged to Urquhard Priory before its amalgamation with Pluscarden. Lord Seton went on to become Earl of Fife and many of the lands round Urquhard are still subject to the 'superiority' of the Earl of Fife today. Feudal baronies were created out of Lord Seton's posessions and the Barony of Urquhard was created, along with a Barony of Pluscarden, and a Barony of Tarnenan [Darnaway]. The Barony of Urquhard encompassed the lands of

| Name | OS Grid Ref. | Extent | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meft | NJ 274634 | ||

| Sallelcot | NJ 275666 | Cotts or Calcotts. | |

| Inays | NJ 279650 | Modern Innes. | |

| Byn | NJ 316646 | Modern Bin. | |

| Garmauch | NJ 337844 | Modern Garmouth. | |

| Locations by Cushnieent. | |||

When the old parish church building became ruinous, in the 19th century, it was determined that a new structure should be built on an eminence known locally as Gashill

When this parish was amalgamated with that of St Andrews-Lhanbryde, there was not further use for the building at Gashill and it, along with the manse, was sold.

(None known.)

1. Mark (2006), p. 722. Return to Text

2. Cosmo Innes uses the same differentiation in the Index Locorum of his Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis'. Return to Text

3. There is a similar 'collection' centred on Burghead/Roseisle and an important concentration in the Haugh of Glass, centred on Invermarkie. Return to Text

4. Morrison (1871), p. 250. Return to Text

5. Prehistoric Find-Sites within 3km. of Urquhard:

| Name | OS Grid Ref. | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Kennieshillock | NJ 302607 | flints; bronze axe; pits; faceted mace-head. |

| Wallfield | NJ 295651 | flints; axes. |

| Wallfield | NJ 295651 | barrw ("The Law"); inhumation with grave goods. |

| Wallfield | NJ 295651 | c.36 gold torcs near the barrow (Middle Bronze-Age, 1500-900BC) |

| Longhill | NJ 274627 | flints; neolithic pottery. |

| Meft | NJ 268639 | flints; neolithic pottery; flint manufactory. |

| Binn Hill | NJ 302653 | cairn. |

| Bogton | NJ 274608 | standing stones. |

| Pittensair | NJ 282607 | "Pitt-" name. |

| Inneshill | NJ 289641 | stone circle. |

| Within a further 3km. of Urquhard are at least four more sites. | ||

| Pitairlie | NJ 247654 | "Pit-" name. |

| Pitgaveny | NJ 240651 | "Pit-" name. |

| Caysbriggs | NJ 245673 | earthwork. |

| Blackburn (Orbliston) | NJ 301583 | cist burial containing 2 gold ear-rings; gold lanula. |

6. Omand (1976), p. 106; Canmore NJ26NE 9. Return to Text

7. Matheson (1905), p. 195. Return to Text

8. Morrison (1871), p. 264. Return to Text

9. Reg. Dunf., nos. 33 and 34, p. 17-19. Return to Text

9b. Pocock (1887), p. 190. Return to Text

10. Exchequer Rolls, i., 14; Firth (2019), p. 4. Return to Text

11. Bartlam (2001), p. 25, where he notes that, "Oram (1996:153) suggests that the coastal quarries between Covesea and Cummingston may be medieval in origin." Return to Text

Bartlam, W. A. (2001) 'Stones and Quarrying in Moray', Elgin: privately published by the author.

Firth, D. (2019) 'Lost and Found: the Barony of Rathenec in Moray', privately published. https://cushnieent.com/articles/rathenec.pdf

Innes, C. (1842) Registrum de Dunfermelyn: liber cartarum Abbatie Benedictine S.S. Trinitatis et B. Margarete de Dunfermelyn, Edinburgh: for the Bannatyne Club. [Reg. Dunf.] https://archive.org/details/registrumdedunfe00bann

Mark, C. (2006) The Gaelic-English Dictionary, London: Routledge.

Matheson, D. (1905) The Place Names of Elginshire, Stirling: Eneas Mackay.

Morrison, J. (1871). 'Remains of Early Antiquties, in and on the Borders of the Parish of Urquhart, Elgin, including Hut circles, Kitchen Middens, Stone Cists with Urns, Stone Weapons, &c., &c.' Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (PSAS), 9, (Nov. 1871), 250-263. https://doi.org/10.9750/PSAS.009.250.263

Omand, D. (ed.) (1979) The Moray Book, Edinburgh: Paul Harris Publishing.

Oram, R. (1996) Moray & Badenoch: a Historical Guide, Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Pocock, R. (1887) Tours in Scotland: 1747, 1750, 1760, Edinburgh: printed for the Scottish History Society. https://digital.nls.uk/scottish-history-society-publications/browse/archive/126602985#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=9&xywh=-332%2C0%2C2410%2C2919

Stuart, J. (ed.) and others. The Exchequer Rolls of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1878-1908. [Exchequer Rolls]

e-mail: admin@cushnieent.com

© 2023 Cushnie Enterprises